A Historic Win in Utah Is Good News for Bears Ears

Read the original article in Patagonia’s The Cleanest Line.

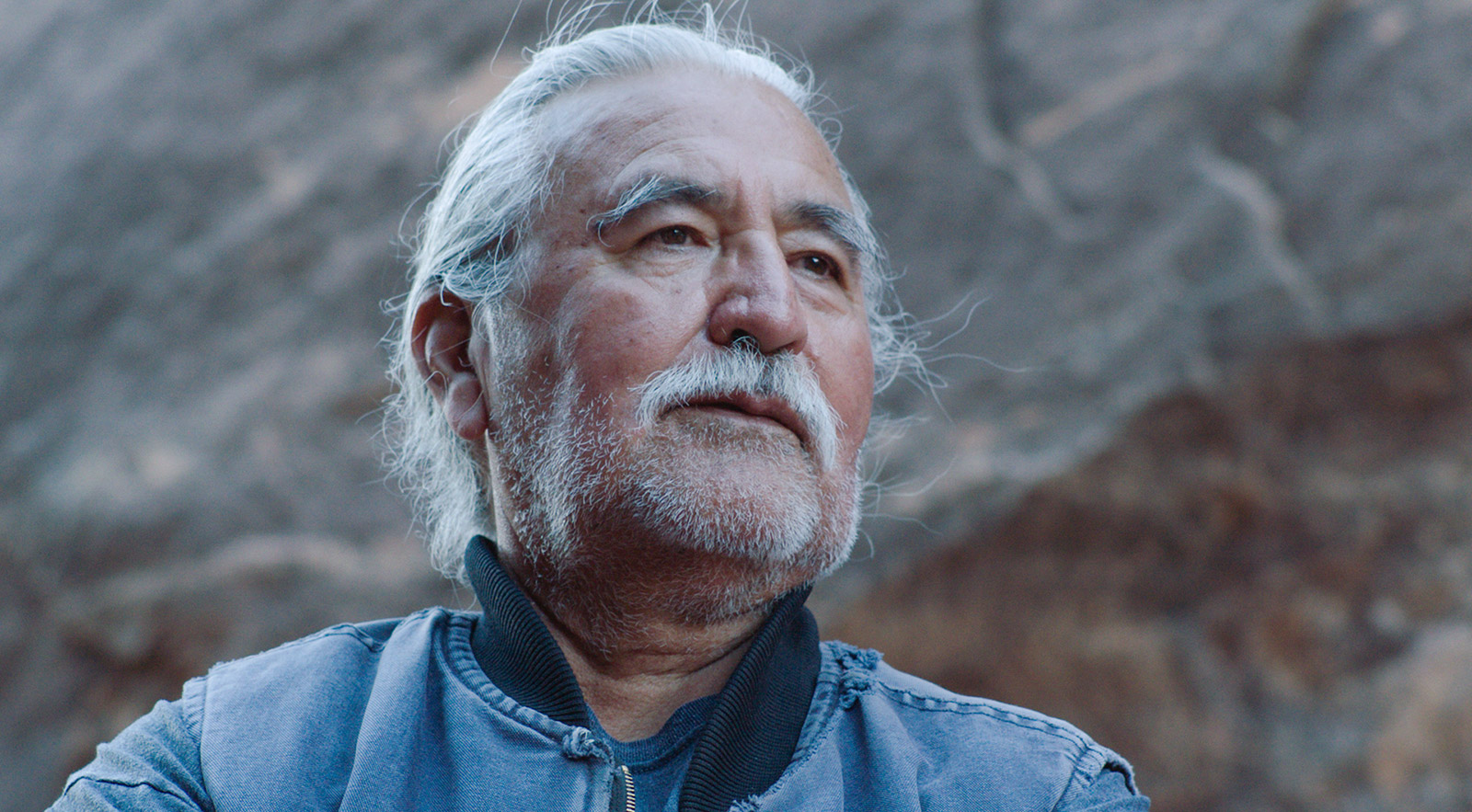

One spring day earlier this year, Willie Grayeyes, a Diné (Navajo) elder with a serious mustache and white hair tied in a traditional bun, stopped to pick up his mail at the post office. Among the usual assortment of bills and catalogs, he found an envelope from the local government of San Juan County, Utah. Grayeyes had recently become the Democratic nominee for a county commissioner seat there, so he guessed the mail had something to do with that. He tore open the envelope and removed a letter.

Rather than confirm his nomination, the letter informed Grayeyes that his candidacy had been revoked. A few weeks earlier, a woman named Wendy Black, a contender for the same seat, had complained that Grayeyes didn’t actually live in San Juan County, a sprawling, sparsely populated pocket of canyon country in Utah’s southeastern corner. Although Grayeyes has voted in San Juan County elections since the early 1990s, Black alleged that he lived over the border in Arizona, because she’d driven to his house, located in one of the most remote places in the Lower 48, and deemed it “not livable.” Based on her complaint, County Clerk/Auditor John David Nielson had asked the local sheriff to investigate. And based on the somewhat dubious results of that investigation, Nielson now wrote, he was denying Grayeyes the right to vote or run for office in Utah.

“If Grayeyes could beat his Republican opponent there, Native American people could control the law enforcement, finances and transportation needs of their ancestral homeland for the first time since Mormon settlers arrived in the nineteenth century.”

On the one hand, Grayeyes was floored. There was no question in his mind that he lived in San Juan County. Yet, at the same time, the effort to strip him of his rights wasn’t surprising when he considered the region’s history. Long after Utah reluctantly allowed Native Americans to vote in 1957, the white, mostly Mormon officials who run San Juan County continued to disenfranchise Native American voters, with far-reaching repercussions.

In 2016, for instance, a federal judge found that the county had illegally packed Native Americans into a single voting district while spreading the white vote across two districts. For decades, this had allowed white voters—who tend to be conservative Republicans here—to elect two commissioners to represent them, while giving Democratic-leaning Diné and Ute voters just one, despite the fact that Native Americans make up 53 percent of the county’s population.

As a result, Native Americans have never held a majority on either the school board or the county commission. Nor have they been appointed to judicial offices or served on cultural or historical boards. White county commissioners have voted down requests to bring basic services such as running water, electricity and road improvements to predominately indigenous parts of the county, and citizens have had to sue simply to get schools built in Native communities. In 1997, a federal official reviewing disparities between the county’s white and Native schools said he “hadn’t seen anything so bad since the ’60s in the South.”

The 2018 midterm elections presented an opportunity to help rectify those disparities. As part of his 2016 ruling, Judge Robert J. Shelby ordered San Juan County to redraw its voting districts, giving residents the chance to elect two Native county commissioners for the first time. District 1 would remain predominately white, and would likely elect a white, Republican commissioner. District 3 would remain mostly Diné, and would likely elect a Diné Democrat. But in District 2, which swung from 29 to 65 percent Diné under the redistricting, the outcome was less certain. If Grayeyes could beat his Republican opponent there, Native American people could control the law enforcement, finances and transportation needs of their ancestral homeland for the first time since Mormon settlers arrived in the nineteenth century.

Did that possibility motivate Wendy Black’s complaint? Grayeyes couldn’t say. He just knew, standing there in the post office, that he had to make things right.

***

Willie Grayeyes was born on March 15, 1946, in an open-air shade house encircled by junipers on land near Navajo Mountain, a dome rising from fissured, sunbaked land near the Utah-Arizona border. Although Navajo Mountain—or Naatsis’áán, “Head of the Earth”—is in San Juan County, it has sheltered Grayeyes’s ancestors for centuries, long before today’s state or county lines were drawn.

Following Diné tradition, Grayeyes’s family buried his umbilical cord in the ground outside the shade house, tying him to the land forever. Grayeyes still lives on that land, though like many residents of this remote community, he travels frequently for work and keeps a PO box through the Tonalea, Arizona, post office because it’s the easiest way to get mail. He grazes cattle at Navajo Mountain, serves as secretary and treasurer of the Navajo Mountain chapter of the tribal government and is school board president of the NaaTsis’Aan Community School. When I asked if he considers Navajo Mountain his home, Grayeyes sounded almost offended. “There’s no doubt about it,” he said.

Equally prominent in Grayeyes’s concept of home is the land surrounding two buttes on the horizon, known as Bears Ears, which also lie in San Juan County. Throughout his life, Grayeyes heard stories about Bears Ears from his grandmother and other relatives—stories passed down through generations about Diné peoples’ ancestral ties to the land. In 2010, when Diné elders broke decades of silence and began speaking about their cultural and historical connection to Bears Ears, in hopes of one day becoming involved in its management, Grayeyes joined their burgeoning movement. A year later, he helped found Utah Diné Bikéyah, a Native American nonprofit dedicated to protecting ancestral lands, including Bears Ears.

After listening to stories from Hopi, Zuni and Ute tribes about their own relationship with Bears Ears, Utah Diné Bikéyah asked President Barack Obama to protect the land as a national monument—an important step toward recognizing that indigenous peoples’ connection to place extends far beyond the reservations they were once forced onto. Shortly before he left office, Obama used the Antiquities Act to designate 1.3 million acres as Bears Ears National Monument. As board chairman of Utah Diné Bikéyah, Grayeyes was thrilled. “It was a win for Native Americans across the country,” he says.

But his joy was short-lived. Last December, President Donald Trump announced his intention to cut Bears Ears by more than 80 percent, a move now being challenged in court by Patagonia, the Navajo Nation and other tribal and environmental groups. Trump also indicated he wanted to downsize nearby Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument by 40 percent.

Slashing environmental and cultural protections for hundreds of thousands of acres of red rock canyons, sagebrush mesas and Native American ancestral sites was a way to “return control to the people,” Trump boasted—presumably local people, like those who live in San Juan County. Before Trump’s announcement, Secretary of the Interior Ryan Zinke toured communities in the county and met with the three commissioners to get a bead on local opinion. The commissioners told Secretary Zinke that the people who elected them didn’t want more protected public land in their backyard. It wasn’t so much that the cultural sites aren’t worthy of protection, says outgoing County Commissioner Phil Lyman, but that “industrial tourism magnates like Patagonia” were imposing their environmental agenda against local wishes.

What Lyman and other county commissioners didn’t mention was that decades of illegal gerrymandering meant their views didn’t necessarily represent those of a majority of San Juan County locals. Grayeyes drove 300 miles to try to meet Secretary Zinke and share the perspective of the region’s Native residents, 98 percent of whom voted in 2017 to keep Bears Ears intact. When he arrived, armed state patrolmen kept Grayeyes from speaking to the secretary.

So, when San Juan County was forced to redraw its voting districts, Grayeyes saw it as an opportunity for residents to elect representatives who actually represent their views. His top priorities as a county commissioner would be to bring better roads and maybe even a new post office to Navajo Mountain. And just as his predecessors used their positions to convince federal politicians to dismantle Bears Ears, he’d use his to support it.

That was the plan, anyway. Then Grayeyes’s right to run for office was revoked, and the county issued a press release saying that criminal charges might be filed against him. Eventually, he sued.

In a region with a history of institutionalized racism, it would be easy to assume that Wendy Black, the county clerk, and the sheriff’s deputy—all of whom are white—wanted to keep Grayeyes off the ballot so that the commission would remain in white hands. But Grayeyes’s legal team argues that the real motivation for derailing his bid for office was his liberal politics and support for Bears Ears National Monument. “He and his organization are proponents of the monument and of public lands and environmental issues,” says lawyer Alan Smith. “I think he was targeted for those reasons.”

Lyman—the outgoing county commissioner whose seat Grayeyes was running for—says he “categorically rejects that premise.”

Yet Grayeyes’s co-plaintiff, a voter named Terry Whitehat, told me that Grayeyes’s stance on Bears Ears was part of his appeal as a candidate. Indeed, while Grayeyes was somewhat reluctant to talk about politics or his own court case, he grew passionate when I asked about Bears Ears.

“Our people have used that land for centuries,” he said. “And the people from the [Mormon] society have less than 140 years. They moved in and totally took it upon themselves to take control of the land. Well, we want to protect those lands, those archaeological sites that are being destroyed. … To this day, we’re still pursuing that.”

***

Ultimately, the ploy to keep Grayeyes off the ballot failed: In August, a U.S. District Court ruled that he be allowed to vote and run for office in San Juan County. A separate lawsuit helped ensure that closed polling locations were re-opened and Native American voters were offered language assistance at the polls. Even so, decades of disenfranchisement and unequal treatment had arguably taken their toll: Native American voter turnout in San Juan County is historically lower than white voter turnout, and no one could say how much the defamatory press release and months of litigation had hurt Grayeyes’s campaign. Heading into the election, his race was too close to call.

Tuesday, November 6, dawned cold and clear in southeast Utah. Representatives from the U.S. Department of Justice, the American Civil Liberties Union of Utah and the state elections office arrived at San Juan County polls to monitor the voting. At Navajo Mountain, Grayeyes sat in the bed of a pickup and chatted with voters as they ate fry bread and bowls of steaming mutton stew.

The ballots rolled in slowly, hauled to the county seat over miles of dirt roads. The suspense was high. When they were finally finished being tallied late last week, though, Grayeyes had defeated Republican Kelly Laws 817 to 648 votes. Along with the election of Diné Democrat Kenneth Maryboy, a Bears Ears supporter from District 3, the victory means Native Americans will soon hold a majority in county government—a first for both San Juan County and the state of Utah. Native Americans also won a majority on San Juan County’s School Board.

The victories were part of a wave of Native American wins across the country. In New Mexico and Kansas, two Democrats—Deb Haaland of Laguna Pueblo and Sharice Davids of Ho-Chunk Nation, respectively—became the first Native American women elected to Congress. Peggy Flanagan of the White Earth Band of Ojibwe was elected lieutenant governor of Minnesota. And despite a law that required voters to have a residential address rather than a PO box, which watchdogs feared would deter Native Americans from voting, indigenous voters turned out in relatively large numbers in North Dakota.

Voters also rebuked politicians who aligned with Trump’s public land policies. Incumbents Rep. Mia Love of Utah and Sen. Dean Heller of Nevada, along with former Rep. Cresent Hardy of Nevada—all Republicans who supported Trump’s decision to shrink Bears Ears and Grand Staircase-Escalante—were defeated by Democrats who ran in part on their support for national monuments and other public lands. (Phil Lyman, however, was easily elected to Utah’s state legislature, and County Clerk/Auditor John David Nielson also won re-election.)

Still, nowhere was the support for Bears Ears clearer than in San Juan County. Just a year after county commissioners told the Trump administration that their constituents opposed the monument, voters rose up to prove otherwise. While the new pro-Bears Ears commission can’t change the monument’s fate on its own, it can reverse the county’s official stance on Bears Ears, making it increasingly difficult for the Interior Department to claim local support. It could even bolster the lawsuit to reinstate the monument’s original 1.3 million acres.

More importantly, though, having two Native American county commissioners could bring a greater measure of equality to the people who call Bears Ears home. After decades of disenfranchisement, a county government that finally reflects the demographics of the people it represents offers progress and hope: Hope that voting rights laws matter, that the reign of settler privilege is crumbling and that desperate attempts to prop up the status quo are futile in the face of informed, engaged citizens.

To understand why Patagonia is in the fight for public lands, please visit patagonia.com/publiclands.