In southern Utah, Navajo voters rise to be heard

Link to Article in High Country News and Buzzfeed News.

Grayeyes’ house is so remote — and often inaccessible, due to weather — that he spends much of his time on the road, sleeping in the car, or at his sister’s house nearby on the reservation. Like so many places in the Navajo Nation, his house has no official address, let alone mail delivery, so he gets his mail at the nearest post office, 70 miles away in Tonalea, Arizona. But that doesn’t mean Navajo Mountain, a community of a few hundred surrounded by deep canyons and a towering mountain, isn’t his home.

Grayeyes was making the two-hour drive to his house from a regional chapter house meeting in Shonto, Arizona, where representatives from six of the Navajo Nation’s 110 chapters hashed out issues concerning their corner of the county. His speed dropped to a crawl as he gestured out the driver’s side window. Grayeyes, now 72, grew up on Navajo Mountain, herding sheep with his aunt and grandmother, and knows every rock. And his efforts to keep his community running dot the rugged landscape: That cell tower? The original plan was to build it in the canyon. Grayeyes negotiated building it on top of the mesa so more of the community could get a signal. Those giant army-green water tanks between the hills? He helped get those built a few years ago — and now they provide the community with much-needed water.

As board chair at Diné Bikéyah, a nonprofit that supports Indigenous causes, Grayeyes has advocated vocally for the full reinstatement of Bears Ears National Monument, which President Trump recently reduced by 85 percent. But most recently, Grayeyes has found himself at the intersection of three lawsuits, different in scope, but with one overlapping goal: allowing Navajo citizens in San Juan County the right to fully and meaningfully participate in a government that was forced upon them more than a century before.

The first suit, brought in 2012, alleged that the county’s voting districts had been unconstitutionally drawn against the county’s Navajo population. A second, filed in 2016, alleged that for many Navajo, voting was so arduous as to violate the 1965 Voting Rights Act. The third, from just months ago, fought to reinstate Grayeyes, who’s running for county commissioner, on the Nov. 6 ballot after he was kicked off following a residency complaint from a GOP challenger.

“Nothing’s easy in San Juan County” — or so the unofficial county motto goes. But when it comes to voting, and governmental representation, it’s been significantly moredifficult for Navajo citizens, who currently make up approximately 51 percent of the county’s population. If Navajos voted Republican, things might be different. But like most Native Americans, they tend to vote Democrat — and thereby threaten the Republican control of a county that hasn’t voted for a Democrat, at least in a presidential election, since Franklin D. Roosevelt, back in 1936.

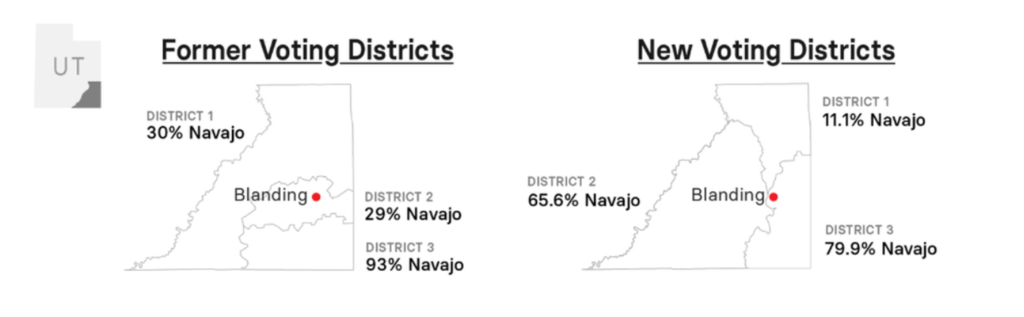

In 1983, the Department of Justice filed a complaint against the county, alleging that its “at-large” elections — in which commission positions were given to the top three vote-getters, whether white, Native, LDS, Republican, or Democrat — disproportionately favored white candidates (at that point, a Navajo had never been elected as county commissioner). Instead of going to court, the county agreed to a consent decree — it would divide itself into three districts: compact, contiguous, and with as equal a population distribution as possible, without fragmenting any “geographic concentrations of minorities.” In one district, Monticello, and the rural ranchland that surrounded it. In a second, Blanding, the most populous city and the de facto center of the county. And in an attempt to follow the agreement, the remaining district traced a boundary for the Navajo Nation, carving out an area whose population, at the time, was 88.77 percent Navajo — a percentage that has since increased to 93 percent. In the 1986 election cycle, the first Navajo in the history of San Juan County was elected commissioner of a district.

The decree accomplished its primary goal: Since 1986, District 3 has always elected a Navajo as county commissioner. The problem, then, is that districting — which San Juan County has repeatedly refused to alter — ensured that there will only be one Navajo county commissioner, always in the minority on county decisions, even as the Navajo population continues to climb. Today, the consent decree provides those in the county who oppose redistricting with an easy defense. If the districts are gerrymandered, opponents say, it’s because the Department of Justice forced them to be that way. If the Navajo don’t want gerrymandered districts, they should go back to the at-large elections — no matter that the county’s at-large elections were precisely what was found to be in violation of the Voting Rights Act.

It’s an argument, according to Leonard Gorman, the executive director of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission, that attempted to prevent “anyone like myself, or my organization, to have an impact on the way they’re doing business in the county.”

“I reject the idea that they didn’t know what they were doing,” Gorman added. “They’re smart people.” That’s why the NNHRC decided, in 2011, to challenge the “packing” of the Navajo district and sued. But it took some convincing for Navajo to believe that change was even possible for the Navajo community in San Juan County. Continual white Mormon control of the county felt like a foregone conclusion. Why try to fight a system that had been historically rigged against them?

But, banding together, and with the help of outside legal counsel, many Navajo here are pushing back. And if the redrawn districts do give Navajo voters a more representative voice in the election process and Willie Grayeyes is elected to the county commission, then Navajo residents wouldn’t just have to push back against the system, they could change it. Because despite being predominantly Navajo, District 2 has always been represented by a white commissioner.

As Dave Conine, former head of the Utah Office of Rural Development, put it, “If Willie wins, and there’s two Native county commissioners, the white people might find themselves very impressed — they’ll see that the Native way of doing things is not going to treat them as badly as they’ve been treated.”

Compared to the state and federal elections currently dominating the news cycle, a race in a county with a population just over 15,000 might seem secondary. But the fight over Grayeyes’ candidacy, and the decades of disenfranchisement that led to it, encapsulates a concern that currently spans the nation. In 2013, a Supreme Court ruling struck down the very heart of the Voting Rights Act, permitting each state to decide its election laws without federal approval. Since then, many states — particularly those controlled by the GOP — have introduced voter ID laws, purged voting rolls, and shuttered polling places. If you don’t live in an urban or suburban area, if you don’t have reliable transportation or mail service, if your work is transitory, if you haven’t voted in every election — it’s never been easy to vote. But now it’s even harder.

These voting changes disproportionately (and often purposefully) affect people of color — especially if they’re poor, rural, or live on a reservation. There’s a reason these new laws, purges, and restrictions are often called “the new poll tax.” For Indigenous populations, it’s nothing new. But that doesn’t mean that the situation unfolding in San Juan County isn’t instructive.

Since its founding, the United States has forced Indigenous people into a democratic system that has done little to serve them. Indigenous populations were excluded from the vote for decades — in many states, until as recently as 1965. Once given the vote, it has been systematically diluted, often through purposeful gerrymandering. This year, a record-breaking number of Native candidates are running for office. At least one— and very likely two — Native women will be elected to Congress, the first in the history of the country. In states like Montana and North Dakota with close Senate races, the Native vote will be a significant deciding factor.

That power, however, has been met with resistance. In North Dakota, the Native vote’s role in electing Democrat Heidi Heitkamp sparked the voter ID legislation, upheld earlier this month by the Supreme Court, which prohibits the use of tribal IDs without residential addresses — even though many Native Americans who live on reservations in the state, like those on the Navajo reservation, have never had an official address. The implicit message: Natives can vote, but only if they do so in the way those in power prefer. It’s an infantilizing and colonial position to take — not to mention deeply counter to the foundational tenets of American democracy.

In many ways, the lawsuits in San Juan County are all fighting for the same thing: to uphold representative democracy, no matter one’s race, or party affiliation, or tribal citizenship, or ruralness, or resistance to existing structures of power. The courts ruled in a way that will theoretically preserve those principles. But in this election, whether in a rural corner of Utah or in states across the nation, they will be put to the test.

WILFRED JONES SAT AT A PICNIC TABLE along the highway in Monument Valley, where the line where the sky and the mesas meet is so bright and blue, so deep and red, that nothing looks real. He’d just finished blessing the new school year at the elementary school across the street. Jones, who is tall and stout in the way that 63-year-old grandfathers often are, is one of the plaintiffs in the redistricting lawsuit, and an Indian boarding school survivor. When he spoke, it was in a deliberate way that could have easily been mistaken for quiet. But speaking deliberately was a survival mechanism from when he was a child in boarding school, where using Navajo words, even the ones that came out naturally on the playground, was strictly forbidden.

“The government people would be standing around guarding you, and they would pull you over, put you in the corner, and give you Lava soap in your mouth,” Jones remembered. Standing in the corner, soap and spit pouring down your chin, trying to keep it from going down your throat and out of your nose made the minutes feel like hours, he said. And if you moved, your time started over. So he learned to be quiet and still.

He spent most of his teenage years in a Mormon foster home, one of over 40,000 Indigenous children baptized and relocated to Mormon homes between 1947 and 2000 as part of what was known as the Indian Placement Program.

For years, Jones generally avoided Blanding and the rest of northern San Juan County, recalling the pain of his childhood there. “When I saw a white man I used to get really intimidated,” Jones explained. “I was taught that because of the boarding school, and it’s really hard to get over and express your opinion. In a public setting especially, in a political setting.” Instead, he looked to his community — and what he could do to change things there. He began lobbying the county to help build clinics, hire doctors, and provide ambulance services for the largely Navajo population in Monument Valley, where paramedics could be hours away. “Minutes is a lot better than hours,” he said. “That’s critical. That’s life and death.”

Jones brought his community’s concerns to multiple public meetings, where the county commission told him something many non-Natives here say all the time: The Navajo don’t pay county property taxes, so they’re not part of the community. That refrain is one of the primary, if unspoken, reasons for opposition to the new redistricting, and Grayeyes’ candidacy: the idea that if Navajo gain power, they will use county funds for projects on the reservation — projects that, since they don’t pay property taxes, some argue they don’t deserve. (When Grayeyes first ran for commissioner in 2012, an ad for his GOP opponent put a fine point on it: “Bruce Adams has been very successful in preventing the expenditure of San Juan County tax money on reservation projects for which the county has no responsibility.” Adams is currently the chair of the San Juan County Commission.)

“That’s ridiculous,” Jones said. “This is the 21st century. Why are we still arguing about who we are? It shouldn’t matter. We’re all county residents.”

Many, but not all, Native Americans living on the reservation do not pay property tax — their land is held in trust by the federal government. But they pay taxes every time they come into town to go to the grocery store, to gas up their cars, to go out to eat. They pay federal income taxes and Social Security, just like every other US citizen; plus, the Navajo reservation pays millions in oil revenue to the county, which is intended to be returned in the form of education and health care. The myth that Native Americans don’t pay taxes is perpetuated so as to absolve those off the reservation from the moral obligation to consider the living conditions of their neighbors.

In 2000, Jones joined together with colleagues to start a nonprofit, the Utah Navajo Health System, now the largest health care provider in Monument Valley. They worked around the county, applying for tribal and federal funds to train volunteers, pay for ambulances, and build infrastructure. The county government refused to help or take their concerns seriously — but they found a way to work around it. But then, in the early 2010s, Jones took his grandson to play in a baseball tournament in Blanding. “That’s when all my memories came back of what I put up with when I was his age,” he said. “Being called all different kinds of names. But it wasn’t as much from the kids themselves as the parents, making derogatory remarks to my grandson.”

Jones was shocked to see the same degree of open racism he’d experienced in the ’70s, only now directed at his grandson. And he decided that instead of trying to navigate the existing county government, he needed to help change who makes up that county government. He didn’t want his grandson fighting those same battles. “Is that how my grandkids are going to have to live? No, we need to do something here,” he said. After that baseball game, Jones contacted the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission and joined the lawsuit to challenge the voting districts. He had had enough.

On Dec. 21, 2017, five years after the initial redistricting lawsuit was filed, federal Judge Robert Shelby ordered the commissioner and school board districts redrawn to more equitably distribute the Navajo population. Two months later, the county reached a settlement in the voting rights lawsuit, agreeing to measures that would facilitate in-person, Navajo-language voting across the county.

As of this writing, San Juan County continues to appeal the new redistricting effort — claiming it discriminates against white residents — at taxpayers’ expense. But the appeal hasn’t stopped the federally mandated redistricting from continuing as planned. In the new District 1, the sitting Republican commissioner is running unopposed to reclaim his seat. In the District 3 Democratic primary, Kenneth Maryboy, who is Navajo, beat incumbent Rebecca Benally (one of a small number of the Nation who supported the reduction of Bears Ears) and will run unopposed.

Which leaves District 2: the most radically redrawn, with a Navajo population swinging from 29 percent to 65.6 percent. It’s also where Grayeyes is running for commissioner as a Democrat. On March 20, a candidate for the Republican nomination, Wendy Black, wrote to the county clerk, John David Nielson, claiming that Grayeyes was not, in fact, a resident of San Juan County. At the time, Nielson did not respond. Instead, after Black lost the Republican primary, Nielson asked Black to file a formal complaint.

In her formal complaint, Black alleged that Grayeyes’ home was “not livable, windows boarded up. Roof dilapidated. No tracks going into home for years.” Weeks before, Black had vocalized a different set of complaints about Grayeyes at the local GOP convention. “He’s going to be a drain on the system,” Black said. “He’s going to want money and a car.”

When Nielson requested proof of residency, Grayeyes, who had been registered to vote in San Juan County for 34 years, submitted printouts of his home’s location on Google Earth, a copy of his birth certificate, and documentation of his cattle operation. In a press release, he invited Nielson to visit his home. Instead, Nielson asked the county sheriff’s office to investigate, and on May 9, decided that Grayeyes was not a resident, and thus was ineligible to vote or run for office in District 2.

The rationale, according to Nielson: Grayeyes had not been home when the sheriff’s deputy had visited, there were no signs of tire tracks or visible habitation, some in the area said he often stayed or lived in Arizona. Nielson’s letter informing Grayeyes of the decision to take him off the ballot was mailed to his P.O. box. He received it 13 days later.

But that wasn’t the end of Grayeyes’ story. In June, he sued to be reinstated on the ballot, citing correspondence between city officials, obtained via a governmental records request, which showed that Nielson had improperly backdated Black’s complaint so as to place it within the legal window for citizens to challenge a candidacy.

Grayeyes’ lawyers alleged that Nielson, the district attorney, the sheriff’s deputy, and Black are all “identified with the historically entrenched political forces in San Juan County, which have fought redistricting in federal court and continue to resist implementation of Judge Shelby’s order.” They all live “north of the river” — the de facto dividing line in San Juan County between Republican and Democrat, anti-monument and pro-monument, (mostly) Mormon and Navajo. The county attorney — Kendall Laws — is also the son of Kelly Laws, the Republican running against Grayeyes.

A federal judge ruled that “virtually no aspect of Nielson’s handling of the matter was legal or within the scope of his role as the county’s top election official.” On August 7, Grayeyes was officially back on the ballot. Yet the question of his residency continues to fester — especially given that the judge did not rule on Grayeyes’ residency, just the validity of Black’s challenge.

To Grayeyes, the idea that someone could look at his home and conclude he hadn’t been there in a long time is not surprising, given how much he is on the road. Yet Grayeyes’ opponents use questions about his residency to cloak a larger concern: that the redrawn districts will fundamentally shift the balance of power within San Juan County. “I feel like we’ve been disenfranchised,” one Blanding resident told the Salt Lake Tribune. “[The judge] stabbed the citizens of San Juan County in the heart the best he could,” Kelly Laws added.

But what, exactly, are these residents so afraid of? If elected, Grayeyes cannot magically restore the size of the Bears Ears monument. But with two pro-monument Navajo on the commission, they would be able to shift San Juan County’s official stance on the reduction — effectively undercutting the federal government’s claim that the reduction was made with local support. In 2017, 98 percent of Navajo surrounding the monument voted in favor of a resolution to maintain its original size. A Navajo majority on the county commission wouldn’t change the attitudes of the majority of the county’s residents. It would just, for the first time in the county’s history, reflect them.

A Navajo majority on the county commission wouldn’t change the attitudes of the majority of the county’s residents. It would just, for the first time in the county’s history, reflect them.

EVEN WITH THE NEW REDISTRICTING in place, there are still many barriers that make it difficult for the Navajo of San Juan County to actually vote. The problem is multilayered: First, there’s the task of disseminating electoral information to Native residents, long excluded from the tradition of voting — and lacking faith their participation could actually change things — and informing them about how the process works. Second, there’s the work of actually registering voters, while also confirming that those who’ve already been registered are in the correct district. Finally, there’s ensuring those who have been registered to vote are able to.

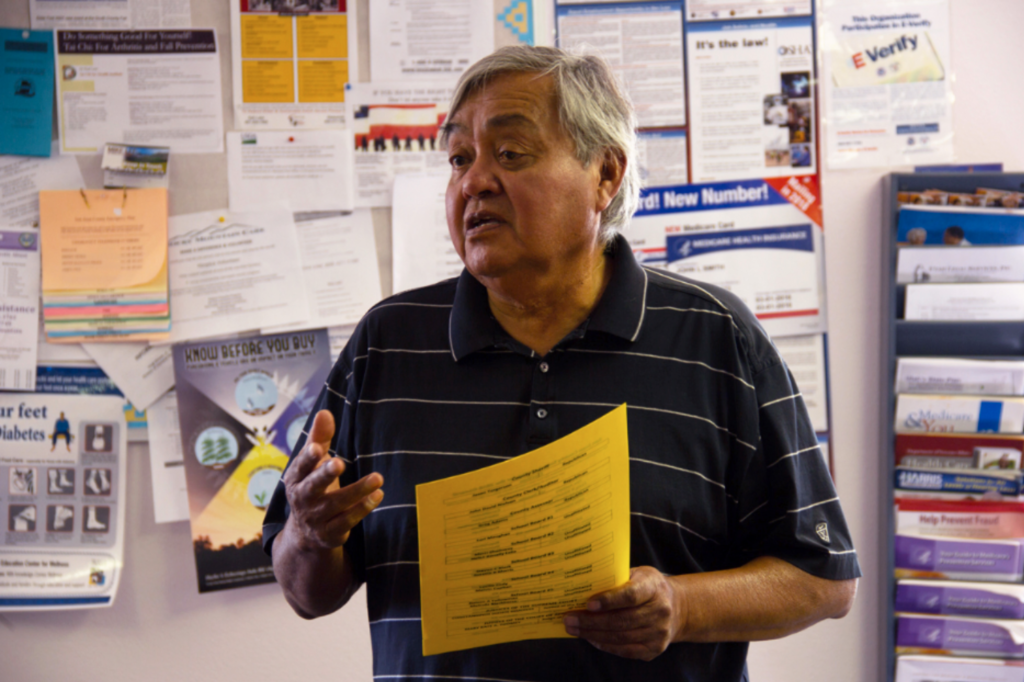

Officially, this work is the task of the San Juan County Clerk’s Office, currently staffed with just three full-time employees, including Nielson. One of those employees, Neal Crank, is the newly hired Navajo liaison and elections coordinator — a position created as a result of the voting rights settlement earlier this year. On a Tuesday morning, we joined Crank as he moved with short, urgent steps while juggling a stack of papers and a bright yellow sample ballot, on a visit to the Bluff Senior Center. Inside the building, a dozen elders had just started their lunch in front of a large television with the sound turned way up. With some reluctance, the group slowly turned their gaze toward Crank, who introduced himself in Navajo and began explaining the candidates running for office.

In chapter house meetings, restaurants, and gas stations on the Navajo Nation reservation, Navajo and English intertwine fluidly. Like many Navajo seniors here, Crank didn’t learn to speak English until about age 6 or 7, when he was in an Indian boarding school. In the summers, his grandmother only spoke to him in Navajo. The only English words Crank spoke to the room of elders were “write-in candidate,” “Nov. 6,” and later, in response to a question, “Willie Grayeyes.”

The Voting Rights Act requires the government to provide ballots “in the language of the applicable minority group as well as in the English language.” Yet ballots here remain exclusively in English — in part because Navajo, like many Indigenous languages, is a historically oral language, and doesn’t have equivalent words for many English terms. That’s why an on-site interpreter is necessary at polling places — and one of several reasons mail-in ballots aren’t effective or preferred by many on the reservation.

Crank has spent months trying to inform as many Navajo speakers as he can on the voting process. Still, he is just one man, and the county is vast. Much of the slack has been picked up by the Rural Utah Project, or RUP, a 501(c)(4) dedicated to voter registration, outreach, and precinct conformation. RUP is headed by TJ Ellerbeck, a veteran political organizer out of Salt Lake City, but 12 of the 14 staff members are Navajo.

As part of their registration work, RUP workers go anywhere Navajo go — chapter meetings, clinics, door to door, major road intersections. The group keeps an otherwise low profile. There’s no homepage or contact information; it doesn’t want to politicize registration any more than it already has been. (RUP’s political PAC, which operates separately from the voter registration campaign, has endorsed Willie Grayeyes for county commissioner.)

Finding unregistered voters and convincing them that voting is worth their time, that’s arduous work. But updating and confirming precinct information is even more complicated, especially on the reservation, where, according to the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission, 85 percent to 95 percent of Navajo voter registrations were geographically incorrect — including 25 percent who had been placed in the wrong district.

The reason for this misdistricting is straightforward, if mind-boggling. Until about 10 years ago, homes in many rural parts of San Juan County, both on and off the reservation, lacked official addresses. To register to vote, you could come into the county clerk’s office, point to your approximate home on a map, and be told which precinct you fell in. If you mailed in your registration, you’d write the closest landmark and indicate how many miles you were from it. When the registration form made its way to the clerk’s office in Monticello, the person there — who likely had little familiarity with the more rural parts of the district — would find the location on a map, then place the voter approximately, but not precisely, in their precinct. Precision, the logic went, mattered less than the precinct.

It was a process that worked — at least until the precinct boundaries changed, and 25 percent of Navajo voters found themselves placed in the wrong district. Many were placed in District 3, where the Navajo candidate is running unopposed, instead of District 2, where they actually live, and where Grayeyes is running a contested race. The misdistricting will also cause headaches on Election Day: If someone shows up to vote in the wrong district, they should still be able to cast what’s known as a provisional ballot. But during the primary election in June, at least one of the polling places ran out of provisional ballots — leaving many without a way to vote. With so few resources allocated by the county, there’s little faith that a similar scenario won’t happen again this time.

Now, RUP is trying to fix the issue, voter by voter, with little assistance from the clerk’s office. To confirm or change one’s district, a voter sits down with a member of RUP, or a representative from the clerk’s office, and zooms in on Google Earth until they see their rooftop. Then, the representative notes the official GPS coordinates, along with the “plus code,” an official number used by the Navajo Nation for emergency services. This might seem straightforward, but it can be time-consuming, especially if the voter does not speak English. “Imagine trying to do this process, through a Navajo interpreter, with an elderly person with little experience of the internet,” Ellerbeck explained. “It does not happen quickly.”

The process also requires an internet connection or cellphone data service — both generally unavailable while going door to door in many parts of the Navajo Nation. In most cases, “unless they come to us, we can’t confirm them,” Ellerbeck said. As of this writing, RUP has registered or location-confirmed over 2,000 voters.

Even if RUP can increase registration and confirm every misdistricted address, it still has to deal with existing barriers to actually casting a vote. Many on the reservation do not have cars or reliable transportation; for some, money spent on gas could instead be spent on food. (One afternoon, we gave a ride to a Navajo woman, somewhere around 70 years old, walking on the side of the highway toward Mexican Hat from Halchita. She was headed to the post office — a 2.5 mile walk down a narrow, winding highway — and planned to make the walk back.) Many roads on the reservation are unpaved; if the road is washed out, there’s no getting anywhere, let alone your polling place.

One afternoon, we gave a ride to a Navajo woman, somewhere around 70 years old, walking on the side of the highway toward Mexican Hat from Halchita. She was headed to the post office — a 2.5 mile walk down a narrow, winding highway — and planned to make the walk back.

“When I was small, it would take almost half a day to travel from Navajo Mountain to Highway 98. In the wintertime or during the monsoon season, it was almost impassable,” said Terry Whitehat, who grew up in Navajo Mountain and served as one of a half dozen plaintiffs in the voting rights lawsuit. “It took at least a whole day to go get your food and come back home.” In a sense, little has changed for Whitehat. According to the lawsuit, his round trip to vote in 2014 was a 10-hour drive. While RUP is coordinating with drivers in and around San Juan County to get voters to the polls, some voters live down dirt roads, more than an hour from their polling place and miles from their nearest neighbor. It takes a lot of drivers to make that many pickups, and that many returns, over such a vast area.

Some rural states have countered the difficulty of in-person voting with expanded absentee options — a fix proposed by residents of Monticello and Blanding. But absentee voting only works if you have reliable access to the mail, which many Navajo simply do not. In September, Gorman told a state legislature committee that an estimated 25 percent of ballots were misaddressed to the the county’s Navajo voters. There are three post offices on the reservation — one in Montezuma Creek, one at a 7-Eleven in Mexican Hat, and one in Bluff. There’s a waiting list for a P.O. box, and most boxes are shared among several people. A man working at the 7-Eleven said half his mail goes to his mom’s box there, and half to a box where his father lives, 45 minutes away, in Montezuma Creek. His mom shares her box with her sisters and other family members, many of whom are off working the oil fields across the Midwest.

As a child, Whitehat was told that participating in the democratic process was how you made yourself heard. “Ever since I was 18, my entire family would go to the poll,” he said. “I would stand in line with my mom and dad, and we would all cast our vote. And that’s a special moment for me. To exercise our civil duties. To me, it’s very powerful, and I want to hang on to that.”

But Whitehat also saw the disenfranchisement of his parents being passed down to him — and, like Wilfred Jones before him, decided the only way the county was going to change things was through legal action.

Whitehat is fluent in English, but his mother, like so many Navajo elders, needs an interpreter to understand the English ballot. Like most Navajo, he remains dubious as to whether that federally mandated interpreter will actually be there come Nov. 6. And there’s similar uncertainty over the reliability of polling places themselves: On primary day in June, the one in Montezuma Creek lost power for lights and air conditioning. The temperature outside crossed 110 degrees. Officials ran out of provisional ballots. The lines grew long and, after waiting in the heat for hours, many withered and gave up. As Janet Ross, currently serving as secretary for the San Juan County Democrats, put it, “You’d think in this day and age, it’d be a lot easier to vote in a place with electricity.”

Like so many other Navajo, Whitehat has canvassed the county to register voters. But he rejects the notion that adequate voting access is something the Navajo must fight for on their own, forcing equal access through litigation, rather than it being a right afforded them like any other eligible American. These might all seem like moderate inconveniences. But inconveniences, no matter how small, disincentivize participation. It’s simple, really: The easier you make voting, the higher the turnout. The harder you make it, the lower the turnout. And right now, in San Juan County, voting remains incredibly difficult.

“THE MORMONS, THEY’VE BEEN HERE, WHAT, 140 YEARS?” Angelo Baca, a Navajo and Hopi activist and filmmaker explained from the Blanding campus of Utah State University. Baca walked over to a mural on the library wall featuring a blown-up black-and-white shot of two young Navajo. “That’s my grandmother,” he said. “She didn’t see a white person until she was 8 or 9 years old. For the Mormons, what happened back then, sure, that’s ancient history. But for our people? It’s like it was yesterday.”

Baca grew up in and around Blanding before leaving for college — first to the University of Washington, then to New York University, where he’s finishing a PhD in anthropology. In 2016, he produced and directed a short film, Shash Jaa’, tracking the effort it took to achieve national monument status for Bears Ears. For Baca, that picture of his grandparents evokes one of overarching tensions that’s come to divide San Juan County: between those — largely white and almost entirely Mormon — who conceive of the events of the past 140 years as history, and those — almost entirely Navajo and Southern Paiute and non-Mormon — who experience the direct ramifications of those events every day, in every aspect of their lives, including at the ballot box.

Recently, it’s seemed more impossible than ever for either side to understand the other. On both sides, that lack of understanding is exacerbated by entrenched resentment of the federal government and distant structures of power, albeit in largely differing ways. Speak to just about any Navajo in San Juan County, and they will tell you a story of boarding school or a Mormon foster home. A house cleaner in Blanding, a jeweler at a stand along the highway in Monument Valley, a health care provider in Red Mesa will recount losing their childhoods, their own children, and their faith to Mormonism. For decades, Native children were sent to Indian boarding schools, often built just miles from their homes, where they were taught English and stripped of their Navajo ways of living and language. It was both condoned and encouraged by the federal government. That forced assimilation was part of a larger, centuries long pattern that could plainly be called genocide or ethnic cleansing.

A different strain of resentment guides the Mormon population of San Juan County. Mormons currently make up more than 75 percent of both Blanding and Monticello, and they dominate the political structures on local and statewide levels. Mormon theology is informed by an indelible sense of persecution — one that started as the earliest believers attempted to forge a community, then codified in 1890, when LDS leaders reluctantly agreed to ban polygamy in order to secure Utah’s statehood. Since then, a conservative, largely rural segment of the Mormon population — including the Bundys, who led the 2014 and 2016 standoffs over federal lands, and many residents of San Juan County — have funneled that resentment toward fighting federal control of public lands.

If you’re not from the West, it might be difficult to process why public lands inspire such resentment. Who wouldn’t want a beautiful forest, or a pristine river, or land you can hunt and fish and camp on in your backyard? What’s wrong with preserving an area, especially in a way that would invite tourists and the economic stimulus that follows? The primary objection rests with originalists’ interpretation of Article IV of the Constitution, which stipulates that the federal government should only own very small amounts of land — not the millions of acres for which they are currently responsible for managing across the West. Instead, they believe decisions about land, and what to do with it, should be made locally — preferably by the county, if necessary by the state. (The Constitution, it should be noted, also protects treaties with Indigenous nations and declares them the supreme law of the land).

Southern Utah, like much of the Mountain West, is a patchwork of various forms of federally owned public lands. There are national parks like Zion (established with great fanfare and collaboration from Mormon leaders in 1919), Bryce Canyon (1928), Canyonlands (1964) and Arches (1971). But there are also massive swaths reserved for the Department of Defense, wilderness areas, Bureau of Land Management (BLM), and national monuments like Grand Staircase-Escalante and Bears Ears. These two sprawling areas are protected via the Antiquities Act of 1906, which empowered presidents to protect Indigenous cultural sites and artifacts, landmarks, and “other objects of historic or scientific interest.”

When Ryan Zinke assumed the office of secretary of the Interior in 2016, one of his first items of business was a “review” of national monuments, with particular focus on those designated by Democratic presidents: Grand Staircase (Bill Clinton), Upper Missouri River Breaks (Clinton), and Bears Ears (Barack Obama). For residents of San Juan County, the review became a flashpoint — for those who opposed the monument, the review was a promise to rectify the wrongs of the past; for those who supported it, a spiteful rebuke.

Which is why today, nearly a year after Trump, on Zinke’s recommendation, reduced the size of the monument by 85 percent, resentment over Bears Ears still lingers. It’s at the heart of every political argument — especially those, like the ones around redistricting or Grayeyes’ candidacy, where people most loudly insist it’s not about the monument.

With residents of Blanding and Monticello, their arguments came into focus. Tourism? Okay in small doses, they argue, but too much and you’ll turn into another Moab — overrun by non-Mormons, restaurants serving liquor, everything, locals say, that Utah isn’t and wasn’t. As for artifacts and sacred sites, they believe they’re already protecting them. A monument simply attracts tourists, which invites disrespect. The BLM? Hostile to ranchers. Wilderness? Too many regulations, and against the sort of recreation (ATVs, snowmobiles) locals enjoy. As for environmentalists, they’re the worst of all: outsiders butting in who want to protect lands that have nothing to do with them, killing local jobs while they’re at it. The sentiment is reflected in Zinke’s official monument review, which dismisses 2.6 million public comments against monument reduction as the work of “a well-orchestrated national campaign.”

There are counterarguments, and counterevidence, to many of those beliefs. In an official Navajo Nation vote, 98 percent of Utah Navajo voters supported maintaining the original size of the monument. Before its designation as a monument, an intertribal coalition argued that Bears Ears was “America’s most significant unprotected cultural landscape,” vulnerable to disturbance. Between 2011 and 2016, for example, the BLM investigated 25 significant cases of destruction, looting, and vandalism in the area, including the removal of a petroglyph with a rock saw, desecration of a burial site, the tearing down of a historic Navajo hogan, and the assembly of a fire ring with rocks from a 2,000–3,000-year-old site). Today, a cave outside Bluff, filled with drawings dating back to the Anasazi, is overlaid with engravings of hundreds of names, including those of several local elected officials.

Yet for many white Mormons, statistics about the looting of sacred sites are eclipsed by more personal events — like a federal raid on a Blanding grave-robbing operation, which ultimately resulted in the suicide of a beloved local doctor — that validate their understanding of the federal malfeasance. And few people in San Juan County are more outspoken about federal overreach than Phil Lyman.

LYMAN, CURRENTLY FINISHING OUT HIS THIRD TERM as a county commissioner, looms large in San Juan County. It was his great-grandfather who founded Blanding, and a solid chunk of town is related to him in one way or another. He’s served as a financial adviser for most LDS-owned businesses in the area, and in 2008, when the Utah Navajo restructured the trust fund for proceeds from their oil holdings, he was the one who oversaw it, traveling with former county commissioner Mark Maryboy to testify in front of Congress.

When the 2017 redistricting ruling came down, it was Lyman’s district — District 2, where Grayeyes is now running against Laws — that was most affected. Instead of running as an incumbent, he’s opted to run for the Utah House, in a district that spans much of southern Utah and its most contentious federal land holdings. In town, he’s put up just a smattering of signs, and done little by means of formal campaigning.

Outside San Juan County, Lyman is primarily associated — to an extent that bothers him — with what’s become known as “The Ride,” when he accompanied Ryan Bundy and dozens of others on an unauthorized ATV ride through Recapture Canyon, a federally protected area that parallels the town of Blanding. In 2007, the BLM had closed the canyon, which is home to numerous sacred and archaeological sites, to motorized use — a decision that struck locals as yet another example of federal overreach. And Lyman’s earned a reputation, even among some Republicans in Blanding, as a slightly boorish, garrulous firebrand.

When asked if he foresaw the county going bankrupt fighting the voting rights lawsuits, Lyman’s response was emblematic of his tenure as county commissioner: “You know, sometimes you do the right thing and deal with the consequences as they come.” The “right thing,” to Lyman and those who support him, is protecting San Juan County from all forms of outside influence — whether from environmentalists, the federal government, the Patagonia outdoor company, or a federal judge like Robert Shelby, who presided over the county’s redistricting, and who previously sentenced Lyman in the Recapture case.

Lyman, echoing many others we spoke with, doesn’t see resistance to the redistricting as racist, or an attempt for him to remain in power. It’s simply the latest battle in the extended war to maintain county autonomy. “You have to be willing to stand up and say, you can do this, but you can’t do this,” Lyman said. “When (the redistricting ruling) came down on Jan. 20, they said the commissioners have to adopt this by Jan. 25. And I said, no we don’t. We don’t have to. They said, if you don’t, they’ll hold you in contempt. And I said, I am in contempt.”

“When (the redistricting ruling) came down on January 20, they said the commissioners have to adopt this by January 25. And I said, no we don’t. We don’t have to. They said, if you don’t, they’ll hold you in contempt. And I said, I am in contempt.”

—Phil Lyman, county commissioner who fought the redistricting of San Juan County

The court did not find Lyman in contempt, but the overarching connotation of the word goes a long way to describe his attitude — and, by extension, the official stance of San Juan County. How dare they? “The whole judge’s ruling was vexatious,” Lyman said, referring to the redistricting. “It’s like, how can we inconvenience San Juan County? How can we inconvenience them more? He’s a federal judge. He does what he wants. For some reason, people act like he’s got authority to do this.”

Federal judges do have authority to rule on county voting issues, particularly if they violate the federal Voting Rights Act. The deeper problem, then, is that Lyman, like many in San Juan County, just didn’t think there was a problem — at least not the one Shelby identified.

If San Juan County is gerrymandered, Lyman says, it’s the federal government that did it back in the ’80s. “The districts that the federal court came up with are at least as unconstitutional as the districts that they were pretending to resolve,” he said.

Even reservations and voter suppression can be fit neatly under the rubric of federal overreach. As Lyman put it, “People will say, ‘Wouldn’t you agree that the Navajo are disenfranchised?’ And I’ll say, oh, yeah, I do agree. They’re put on a reservation. They don’t own their own land. They had their sheep slaughtered by the federal government. But all these things, all these issues we’re talking about, San Juan County didn’t do that. That’s the federal government.”

It’s a common view in San Juan County: The treatment of Indigenous people by the federal government is wrong, but their treatment of Native people is right. The forced redistricting suggests that Navajos had not already been equal citizens within the county — a belief Lyman cannot abide.

In his view, he said, “Native Americans in San Juan County are the same as anyone else in San Juan County. We all live here, side by side. I don’t see a difference.” But, he allows, “The truth is, there is racism. There’s paternalism and arrogance and insensitivity, all of those things.”

According to Lyman, however, that racism does not flow from the county government, or from him. When asked if he believes there should be more Navajos in the electoral process — as candidates, and as voters — his answer was unequivocal. “Yes,” he said. “Absolutely, yes. When I ran for commissioner, I stood up in the Republican convention in a room full of old white Mormon guys, and I said, the future of San Juan County is south of the river. And until we learn to appreciate the culture that has so much to offer, we’ll be living below our potential.” (Conversely, almost every Navajo interviewed for this story agreed that Lyman was unwilling to see things from their perspective.)

What Lyman can’t reconcile, then, is the ruling — which attempts not just to appreciatethe Navajo, but allow them representation that reflects their population within the county. Again, he argues that his contention, like his previous resistance to Bears Ears, isn’t with change, but with outsiders in charge of trying to change it.

“We don’t negotiate with a gun to our head,” Lyman said. “Process is more important than the product. And this nation places a high premium on consent. You don’t tell somebody, if you don’t give me what I want, I’m just gonna take it. That can create some really hard feelings.”

And yet, for the Navajo, that’s exactly what happened when settlers first arrived. It’s why, today, they’ve resorted to these lawsuits: They’re a means of pushing back against a more modern form of colonialism, using a form of communication — the legal system — even the most entrenched forms of power can’t ignore.

ON OUR LAST DAY IN SAN JUAN COUNTY, the sun climbed high in a blank blue sky as Grayeyes showed us the land he calls home. He drove past the Navajo Mountain Chapter House down a narrow, sandy road, beyond a wire gate, and past the remnants of a different time. He stopped and led us to a squat, circular building and opened the door. Inside were tattered books scattered across the floor, the remains of the boarding school where he was sent as a young boy in the 1950s. “That was the first time I saw a white person,” Grayeyes recalled. “And the first time I heard English.” Navajo Mountain, all 10,387 feet of it, loomed behind us. Earlier he’d bragged that when he was young, he’d leave early in the morning, go up one side, then run down the other.

We got back into the car and pressed on, further down the road, where we passed a new school, built only after a judge ordered the county — which, as late as 1995, claimed it was not responsible for educating Navajo children — to do so. Grayeyes drove to the edge of the canyon, past where the pavement ends, as a man on horseback slowly trotted by, and pulled over. You need a truck to get to his house in the valley across the canyon, he said.

“No way I’m taking my good car out there,” he said with a grin before scrambling to the top of the ridge, his white hair gradually coming loose from its tie in back. He skillfully pushed through brush and up the rocky terrain, pointing out the different landmarks — an old game trail, the way wagons used to make their way to the valley — in the sprawling reds and grays of the canyon. On the road below, a pickup, saddled with a massive container of water, meandered past.

Earlier in the week, Angelo Baca had explained what he saw as the heart of the fight against Grayeyes. “They’re really drawing the line between who they think is civilized and sophisticated enough to hold office,” he said. “And they don’t think Willie is, because he’s a very traditional guy. But, let me tell you, that guy doesn’t miss anything. He’s a freaking hawk. He’s got your number, as soon as you’re sitting down with him.”

“Let me tell you, (Willie Greyeyes) doesn’t miss anything. He’s a freaking hawk.”

—Angelo Baca, Navajo and Hopi activist and filmmaker

Democracy is often referred to as “The Great American Experiment” — an experiment, many often omit, built on the enslavement and extermination of people of color. Historically, the times when the experiment has been most meaningfully tested have corresponded with the times when those same people of color have challenged the status quo, forcing a reconsideration not only of who deserves a voice within the larger experiment, but who deserves to benefit from it. We are, right now, in one of those times. The resistance to the Native vote — like the resistance to the black vote, or the Latino vote — just shows how powerful that vote is, and just how much work has been done to subvert it. Today, the endurance of American democracy doesn’t just hinge on shifting the lines of a district or facilitating the ability to vote. It’s contingent on a willingness to acknowledge — and share — the power that stems from it.

Grayeyes sees what’s happened — what’s happening ahead of this election — very clearly. When he responded to his removal from the ballot, he noted that connection to the land is more than just the brick and mortar of a home or the ink and paper of a deed. While his mail is delivered to the Arizona side of the border, his home is in Navajo Mountain, where he was brought into the world and where his umbilical cord is buried.

The Navajo bury umbilical cords in their birthplaces so their children will always know where their home is and can always find their way back. They’ve been doing this for generations. The way Grayeyes sees it, the county officials up north have rarely — if ever — taken the time to understand the Navajo, their needs, or their lives.

Lyman says he’s made efforts to understand life on the reservation. But his comments suggest otherwise. “You don’t say, here’s where my umbilical cord is buried,” he said. “When what you should say is, here’s my utility bill from my house in Navajo Mountain, or here’s my driver’s license.”

But Navajo Mountain is where home is, Grayeyes said, even if it has no electricity or an address to send an electricity bill to. And he wants to help his home and community as county commissioner — and believes he’s the best person to do so. He wants to expand economic opportunities in the county; he wants to create new jobs. And he maintains that if he wins, there are only a few non-Native residents and colleagues he’ll have to win over. Most county residents, he believes, understand that the way the Navajo are treated here needs to change.

He wants the others to recognize the legacy of colonialism and why the Navajo Nation reservation even exists. The intent, he said, was to eradicate the Navajo. But, he said, “We kept our languages, our songs, our ceremonies, our thinking patterns. They have tried and tried and tried. But we’re still here.”